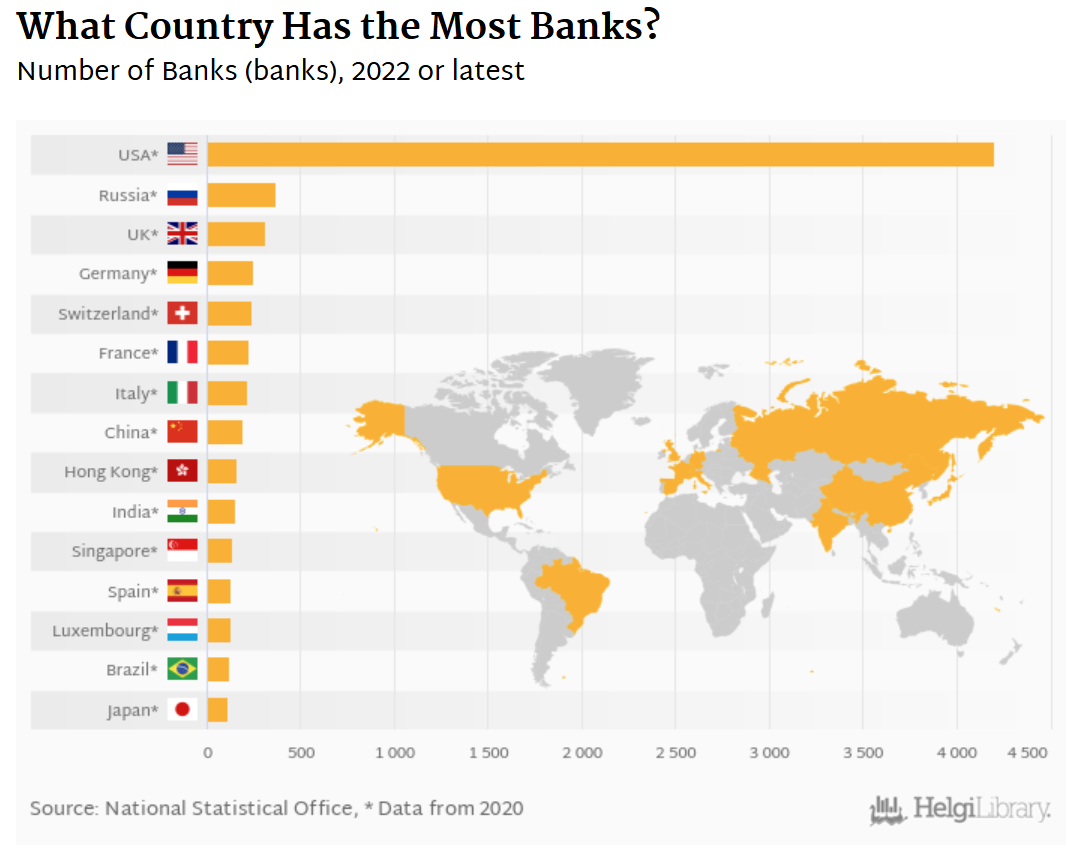

Can I say something without everyone getting mad? I think we have too many banks. At over 4,000 commercial banks, America has more banks than the next 14 biggest countries, combined. That combined with a whopping 80,000 bank branches, means that Americans should be the most well banked beneficiaries of the principles that have encouraged the proliferation of this massive banking system. But is that actually the case?

Proponents of having more banks in a financial system often focus on variants of these three core arguments:

More banks increase access to banking services and promote innovation

More banks increase competition and asset diversification

More banks reduce regulatory risk and operational burden

With this over-engineered deep dive, I’m no longer convinced that these arguments hold true and that more banks are actually beneficial for the American banking system. In fact, more banks may actually cause more risk to our financial foundations, as we’re already seeing from the string of bank collapses, regulatory actions and impact to customers.

Of course, I think there is power in a diverse banking system so total consolidation is not the answer. And I think there’s a role for GSIBs, regional banks and community banking organizations in that system. But the total number of banks should be closer to 1,000 than 4,000 (and I’ll show you the math and policy that gets us there). Curious how it all plays out? Let’s get bank to it.

(Note: For the purposes of this evaluation, I’m focusing on commercial banks across countries as they are most commonly associated with how we think about banks, are for-profit entities with the broadest financial product offering and have most consistent regulatory framework and metrics. If you’re seeing different numbers than the ones I report, it may be because the US and other countries often have a broad network of credit unions / credit institutions, savings institutions and other “bank-like” institutions [which can skew reported metrics on number of banks]. This doesn’t change the nature of the argument, because the US likely still has the most banks of all types of any country with over 4,900 credit unions and 600 savings institutions on top of the 4,000+ commercial banks, but it does help standardize the metrics).

Do More Banks Increase Access to Banking Services And Promote Innovation?

It’s true that more banks can increase flexibility and community banks especially can tailor services to their constituents. Yet despite having the most bank branches per capita among any nation (~4x the median), among World Bank countries, the US ranks 30th for percentage of people with bank accounts, 33rd for percentage with debit cards, and 9th for percentage with credit cards. Even for small business lending, an area where America’s nearly ~3,500 community banks have shone among their larger bank counterparts, the US is still second to last on the scorecard for OECD countries in small business lending as a % of total lending. So it seems to be the case that more banks doesn’t necessarily mean more banking service access, despite the heartwarming anecdotal stories. In fact, the fact that there are so many, often very small banks without economies of scale, may actually make it harder to effectively serve their constituents (a point we’ll discuss in more detail later on).

On the financial services innovation side, the comparisons are unfortunately quite similar. The US still lags behind China, India, the UK and Germany when it comes to mobile payments adoption. Meanwhile, US adoption of real-time payments still lags significantly behind other global regions as more than 60 other nations have adopted faster payment options. In this case, having more banks likely increases technological implementation issues, complicates regulatory oversight and reduces network effect benefits since there are thousands of banks to implement and standardize against. Indeed, when evaluating the slow adoption of FedNow, the often-cited reason for slow adoption has been that there are just so many more financial institutions. So again we find the more banks doesn’t necessarily mean better innovation on the banking and payments innovation side.

Do More Banks Increase Competition and Asset Diversification?

A central argument for having more banks is around improving competition and increasing asset distribution as a result. And it is true that when comparing bank asset diversification among the nation’s top 3 banks across countries, the US is in the top 10 nations with diversification among banks, with ~38% of assets concentrated among the top 3 banks. That’s certainly compares favorably to European counterparts like Germany (79%) and France (66%) but is only a bit better than India (41%), UK (43%) and Japan (46%) despite them having less than 1/10th the number of banks. Of course, 38% is a large number on its own and it certainly doesn’t feel like having 4,000 banks is creating the diversification you’d expect.

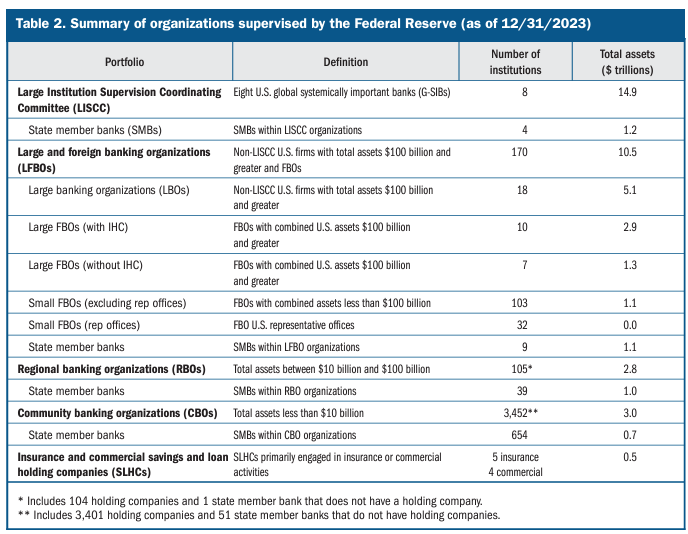

As we double click into the US financial system details, the numbers only get more worrying. Notably, 8% of banks hold 91% of bank assets, and 43 banks have at least $100bn in assets and comprise 76% of total bank assets. These large financial institutions own 50% of the total bank branches and ~70% of outstanding loans and leases, despite the number of banks in the ecosystem.

So it doesn’t seem to be the case that more banks are leading to any more competitive distribution of assets. Between basic economies of scale, lower costs of deposits (by nature of scale and distribution) and other dynamics, the prevalence of more banks has not changed asset concentration.

Do More Banks Reduce Regulatory Risk and Operational Burden?

Some argue that the abundance of banks also leads to reduced regulatory risk by creating a more distributed financial system. But that can only be true if the regulatory system is designed to efficient regulate its constituents. In the case of the US, where the FDIC is responsible for regulating ~91% of the community banking organizations that are not members of the Federal Reserve system (~2,700 institutions), each bank is examined every 12-18 months by a number of examiners with the median examination lasting ~64 days. But the FDIC only has 5,280 total employees, of which only ~54% are examiners, which means there’s only an average of one examiner per community bank at any given time.

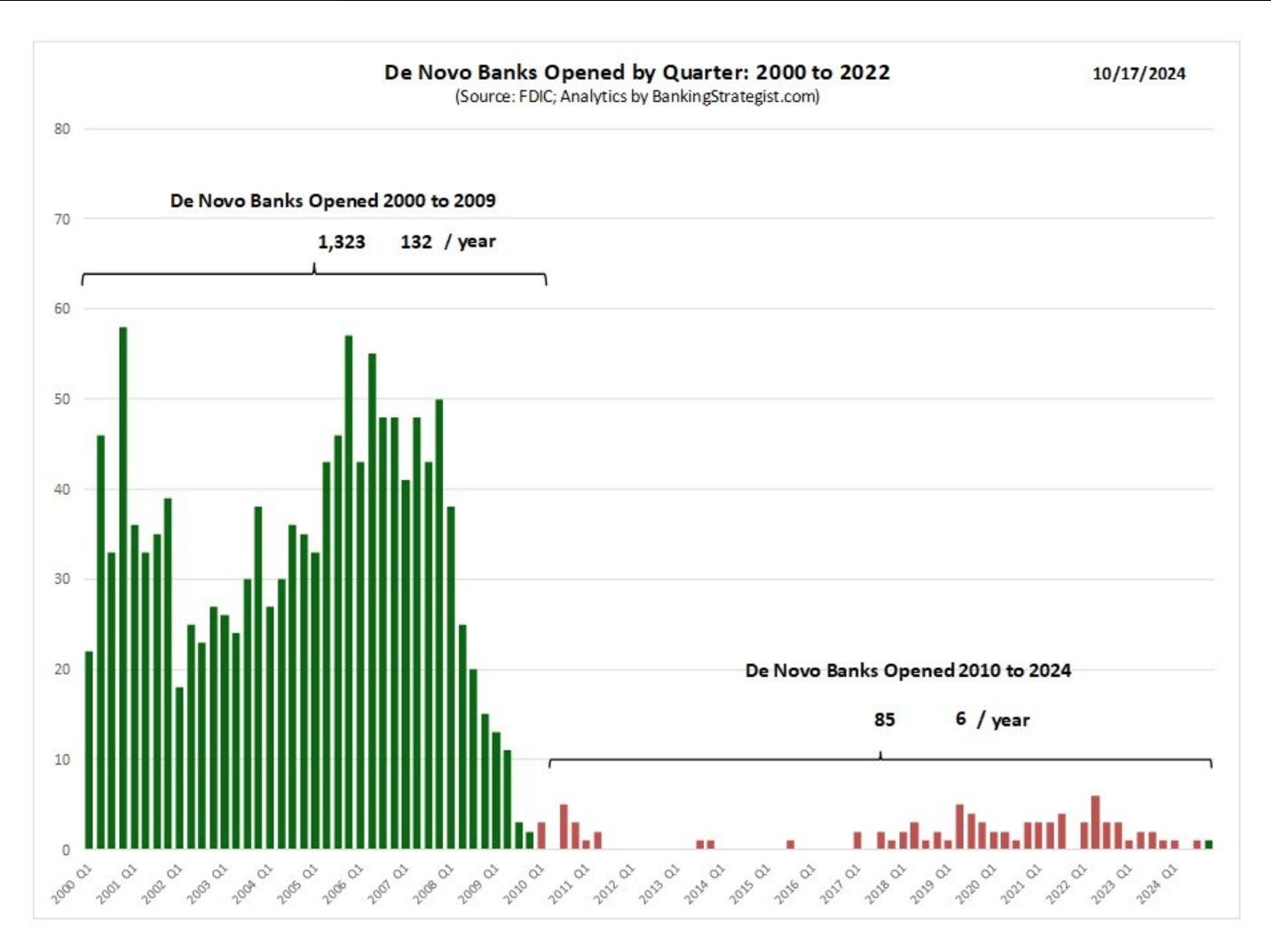

With those statistics in mind, the approval rate for de novo charters makes a lot more sense (~4 new banks for every 100 bank closures) - there’s just not enough resources to manage the existing bank base. But of course, between the recent spate of community bank consent orders and BaaS bank related regulatory actions, it’s clear that regulatory agencies are still playing catch-up when it comes to monitoring this vast bank base.

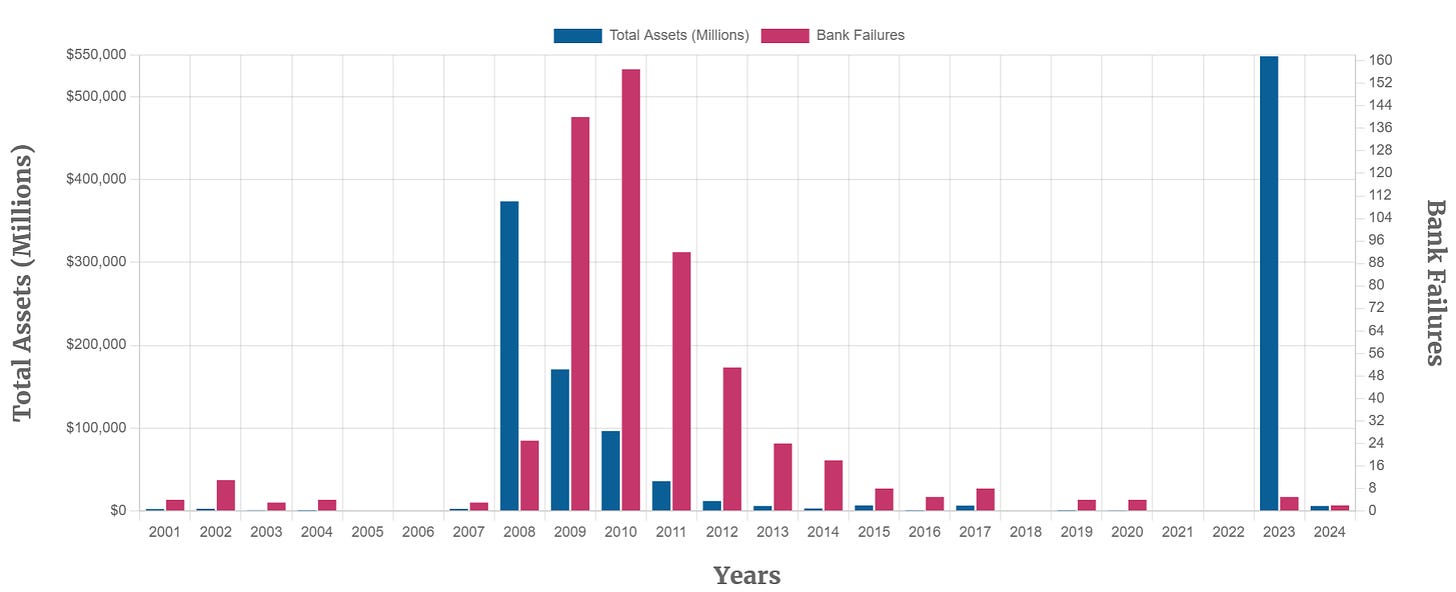

When it comes to bank failures, despite what is described as a highly regulated financial system, the US has experienced more than 500 bank failures in the past 15 years, amounting to ~13% of the total banks in the country, and includes both community banks and major regional banks, suggesting that the sheer of banks can stymy the regulatory system. Other nations like Canada and Japan have experienced zero bank failures while the UK has experienced five over the past 15 years, leading to failure rates that are lower than the US.

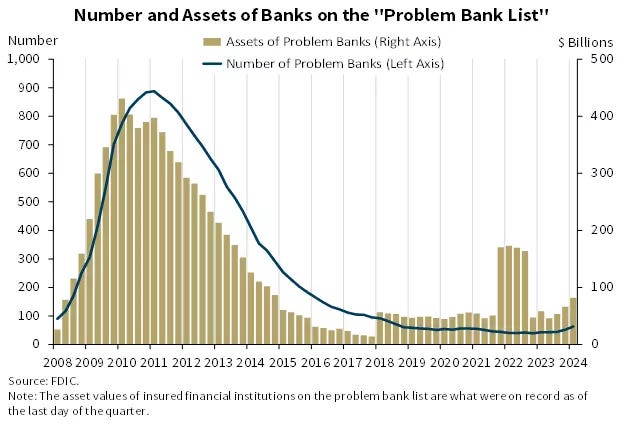

Moreover, the number of FDIC “problem banks” (banks that have a high risk rating due to financial, operational or managerial issues) has stayed stubbornly consistent since 2018 and assets held at these problem banks has actually increased substantially in the past five years.

Far from reducing regulatory burden and diversifying financial system risk, it seems that our multi-thousand banks strategy isn’t generating the benefits we expect.

The Magic (Bank) Number: 1,000

So it seems to be the case that more banks haven’t necessarily lived up to the idealistic promises we envisioned around (1) increasing access to banking services and promoting innovation (2) increasing competition and asset diversification and (3) reducing regulatory risk and operational burden.

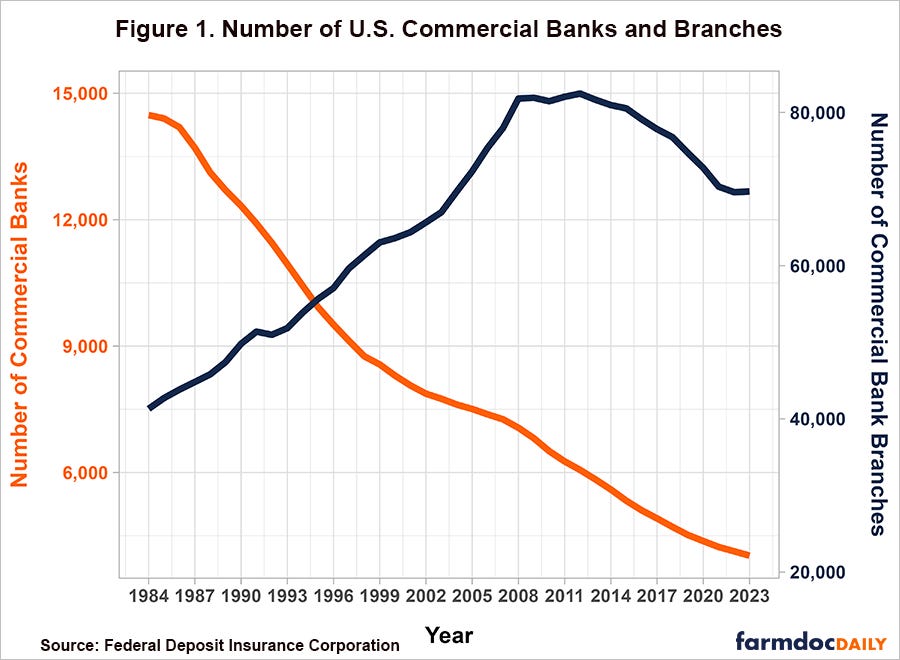

While the number of banks have declined precipitously since the 30,000+ banks we had in the 1920’s as a result of branch banking limiting laws and gone down another ~70% since 1984, it’s clear that there’s still too much burden on our financial system to support this many banks. Of course, if bank consolidation goes too far in the other direction, we could just magnify the too-big-to-fail problem and further consolidate assets in all the wrong ways. So what’s the right number of banks and how do we get there?

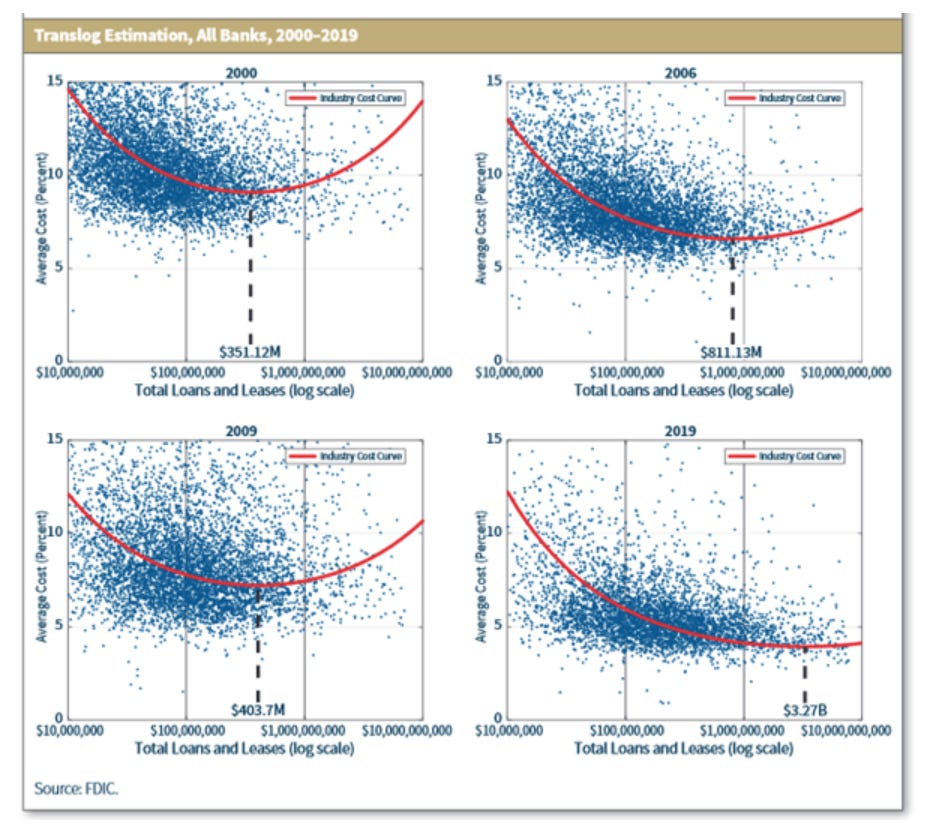

As a first step around intelligent consolidation, let’s apply the principles of economies of scale. It turns out that per the FDIC, banks only start accruing economies of scale on loan costs when loan portfolio’s exceed $300M and the optimal loan portfolio balance is ~$3.2bn for ideal unit economics.

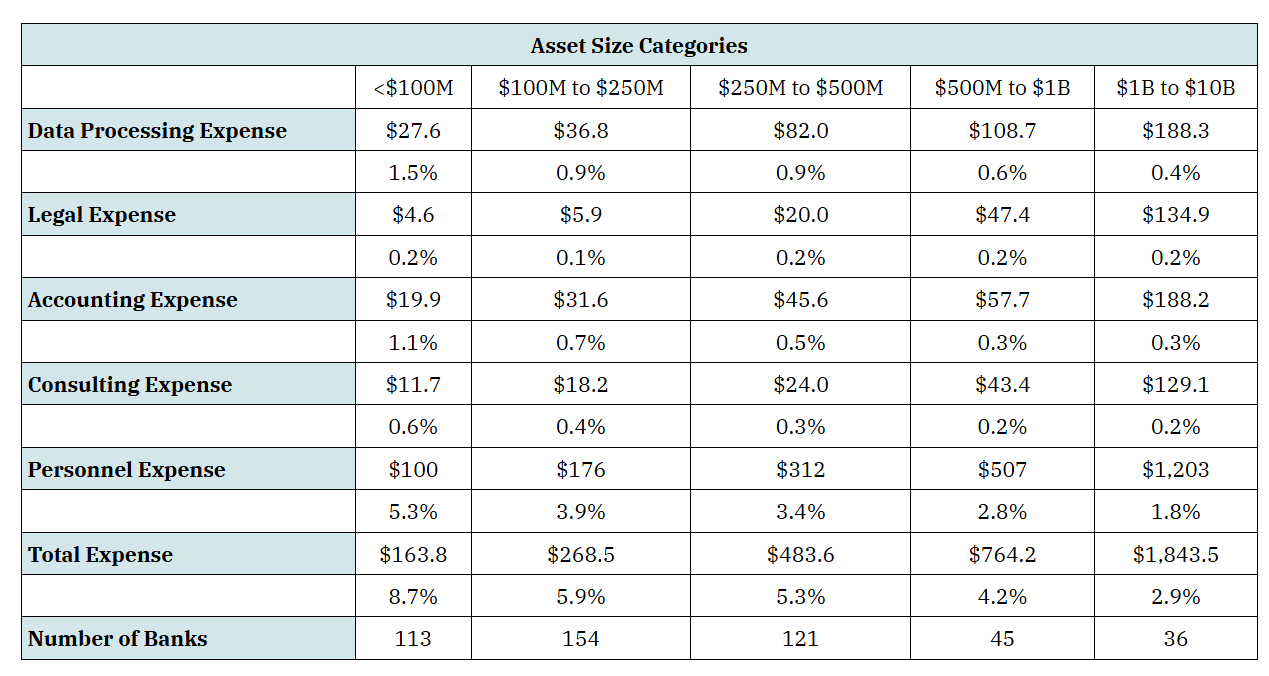

That means both that community banks must be of a certain minimum size to achieve economies of scale to benefit their community, but also that they can achieve that scale at community bank size ($1 - $10bn in assets), right around ~$600M - $1B. Similarly, when it comes to compliance, legal and personnel expense, banks that had at least $1B in assets had 30% lower expenses than banks with $500M - $1B in assets and up to 2x less costs than banks with <$250M in assets. Finally, while a recent FDIC study indicates that large bank mergers can be detrimental to bank resiliency and increase net charge-offs, they found that with bank merger <$1B, there was no impact on financial resiliency.

So as a first step towards consolidation, we should institute a minimum asset threshold of ~$1B in assets among established banks and encourage targeted mergers among remaining banks, but we should also require de novo bank approvals to increase substantially. Given ~23% of community banks have at least $1B in assets, we’d be able to reduce total banks by ~2,700 while likely increasing bank service access and improving competition as banks can become more operationally efficient and financially stable. In addition, the consolidation among established banks would allow de novo bank charter approvals to increase substantially to properly offset bank failures and closures, allowing new bank entry that would promote innovation (these banks would get a reasonable ramp period before they’re required to hit the $1B asset threshold).

As a second layer of consolidation, all state chartered banks should be required to become state member banks of the Federal Reserve. This additional regulatory requirement would increase regulatory standards by having state banks be subject to state and federal laws and allow for the Federal Reserve’s additional 825 examiners to supervise these banks (while the FDIC normally oversees non-member banks, in this new system every bank would be a member bank which would just increase resourcing). Over ~654 community banks are already state member banks (SMBs), so with the asset-based threshold, I’d bet the overlap is strong enough that this wouldn’t be an incremental requirement for most banks. In addition, being a part of the Federal Reserve system allows for direct access to Federal Reserve money movement systems like ACH clearing and FedNow instant payments, which will increase adoption rate among smaller banks.

All-in, we’d have 8 GSIBs, 170 large financial banks, 105 regional banking organizations and ~650 - 800 community banking organizations, a grand total of ~1,000 banks. All banks would have a scale large enough to have economies of scale to keep costs low for their customers. All banks would be regulated by two federal agencies with ~5x the regulatory oversight, without onerous incremental requirements. All banks would have direct access to faster money movement systems. And new bank charters would finally be able to be approved at a rate that can offset bank failure and closure rates.

Of course, as with any large-scale regulatory and ecosystem change, it could be pretty difficult to make something like this happen, even with the obvious benefits. Still, there’s hope that with a desire to catch up to our global peers and build a better banking foundation for all, we can make the tough decisions to get actual change. Are you banking on it?

The industry is consolidating though, driven exactly by scale economics, just not as fast as it should? Are you arguing that regulatory obstacles are too high for mergers?