The impossibility of 3%

I have a lot of respect for consumer fintechs that make a business out of selling a product for free. It’s tough to figure out how the ecosystem can pay for the service you’re offering in a way that allows you to give it to your members for free. The only way to be able to do that successfully is for companies to fully understand the underlying unit economics of the business and what levers there are to increase margins so companies can offer even more without charging more.

Cash App made fast, free P2P work for consumers and changed how we think about the value (or cost?) of instant payments (I don’t say Venmo here because I don’t think Venmo ever figured out the “business” of profitable P2P before acquisition). Chime launched SpotMe to enable free overdraft and got the entire bank industry to start reducing or eliminating overdraft fees. And Robinhood ushered in the era of zero free stock trading that ultimately caused every major brokerage to eliminate them as well (and even resulted in a wild TD Ameritrade acquisition only a month later).

So I find it somewhat confusing that even despite every fintech nerd understanding that modern fintechs have been making businesses work under the price of free, when Robinhood introduces a 3% cash back credit card after acquiring X1 (which I always thought was a no-brainer), they seem to forget everything and deem it impossible to make high cash back rewards work profitably. They’re almost eager to assume that this can only work as an acquisition driver or a lever to drive cross-sell on other products on their platform.

Now I think Mahdi Raza of Exponent Capital intelligently lays out the economics of Robinhood’s Gold Card as a whole, saying that it’s possible for Robinhood to get at least a ~36% margin on the card, but it does assume a ton of funding from merchant rewards and it does depend on some revenue from the revolving balances to offset charge-offs. So fintech nerds can look at this math and still conclude that the core value prop of 3% cash back is unsustainable.

But I actually think Robinhood can make a more bold claim. I think it’s possible for them to pay for the 3% cashback entirely from card spend. And I think all the folks who don’t think it’s possible have relied on a brilliant yet overly simplistic way of looking at the equation, based on Matt Jones’s take on credit card rewards.

In his mind the equation is simple - when your interchange fee is 2.2% and your cashback is 3%, the math just isn’t going to math. But is it really that simple?

There’s more to this unit economics story, and I’ve got the breakdown of the 4 elements that make it possible for Robinhood to pay for 3% cash back with just the card spend alone.

(Note - for the purposes of this analysis, I’m only looking at the net revenue margin for the business - take rates on card spend less cashback. I’m not digging into cost of capital or losses/chargebacks as that happens at the COGS/contribution margin level, because I’m trying to prove that you can pay for high cashback at the topline level. I may get into the other detail in another post).

The Unit Economics of Cashback Rewards

The right side of the equation is not quite right because as always it’s about more than just interchange.

(1) Interchange Fee

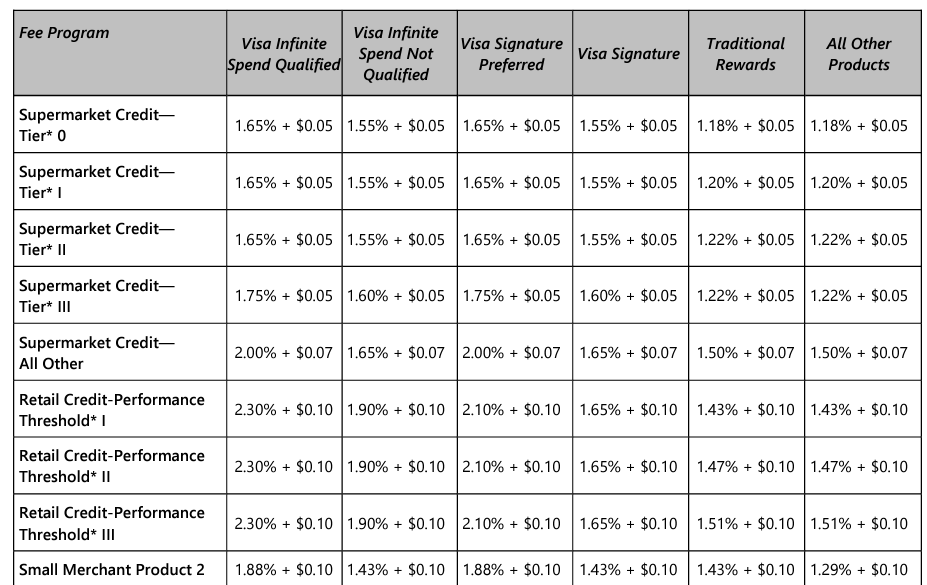

Let’s start with the biggest assumption built into this equation, the interchange rate, which everyone in the fintech world has seemed to have decided is 2.20% (interestingly Simon Taylor, Alex Johnson and others all reference this number without a source). Where does that number come from? If someone says it’s from an interchange table, I would want to know how the heck they were able to derive anything of substance from a table like this:

As Patrick McKenzie says in his brilliant post about credit card rewards:

You can just look up the rates, but I strongly recommend you don’t, as you will be reduced to gibbering madness. (It took many smart people many years of work before Stripe could deterministically predict almost all interchange it was charged in advance of actually getting billed for it.)

So it’s reasonable to say that the rate isn’t from the interchange table. Maybe it’s from this widely quoted NRF article which mentions that “Swipe fees for Visa and Mastercard credit cards currently average 2.22% of the purchase amount.” But that’s a 2022 article that mentions a 2021 Nilson report - the latest is ~2.26% from the report as of 2023 (already got 6bps back in the bank!).

But it’s not even the full story, because that’s just the average credit card interchange rate, representing the average credit card. And the average credit cardholder has a FICO score of 715, uses Chase as an issuer, pays on the Visa network and doesn’t carry an annual fee. (as an aside, this was one of the hardest data points to find).

In other words, the average credit cardholder is probably spending on a Chase Freedom Unlimited card (which is actually much better than I thought - 1.5% back on everything, 5% on travel, 3% on dining, 3% on drugstores with no annual fee).

Why did we just go down this rabbit hole? Well, one thing you’ll notice about that card image is that it just says “VISA,” not “Visa Signature” or “Visa Infinite”. That’s important because it means that (A) the average credit card generates 2.2% interchange and (B) the average credit card is a Visa Traditional Rewards card.

That matters because different Visa tiers earn different interchange rates. And we know from both the website itself and their terms and conditions that Robinhood’s card is at least a Visa Signature card. In fact, based on the quality of their benefits (purchase security, return protection, roadside dispatch vs assistance), Robinhood’s Signature card could actually be a “Signature Preferred” card which sits between Visa Signature and Infinite but puzzlingly has no visual identification and does not carry any specific differences in requirements per Visa Core Rule Book.

While we won’t use the absolute values to determine rates since the interchange tables are so different from the swipe reality, we can say that Visa Signature cards probably earn at least ~10% more interchange than Traditional Rewards cards and up to 40% more interchange if they are a Signature Preferred card.

So let’s split the difference and apply a haircut to be safe with 15%.

So 2.26% * 1.15% = 2.60%. Already seeing 40bps higher interchange rates than everyone thought and we’re just getting started.

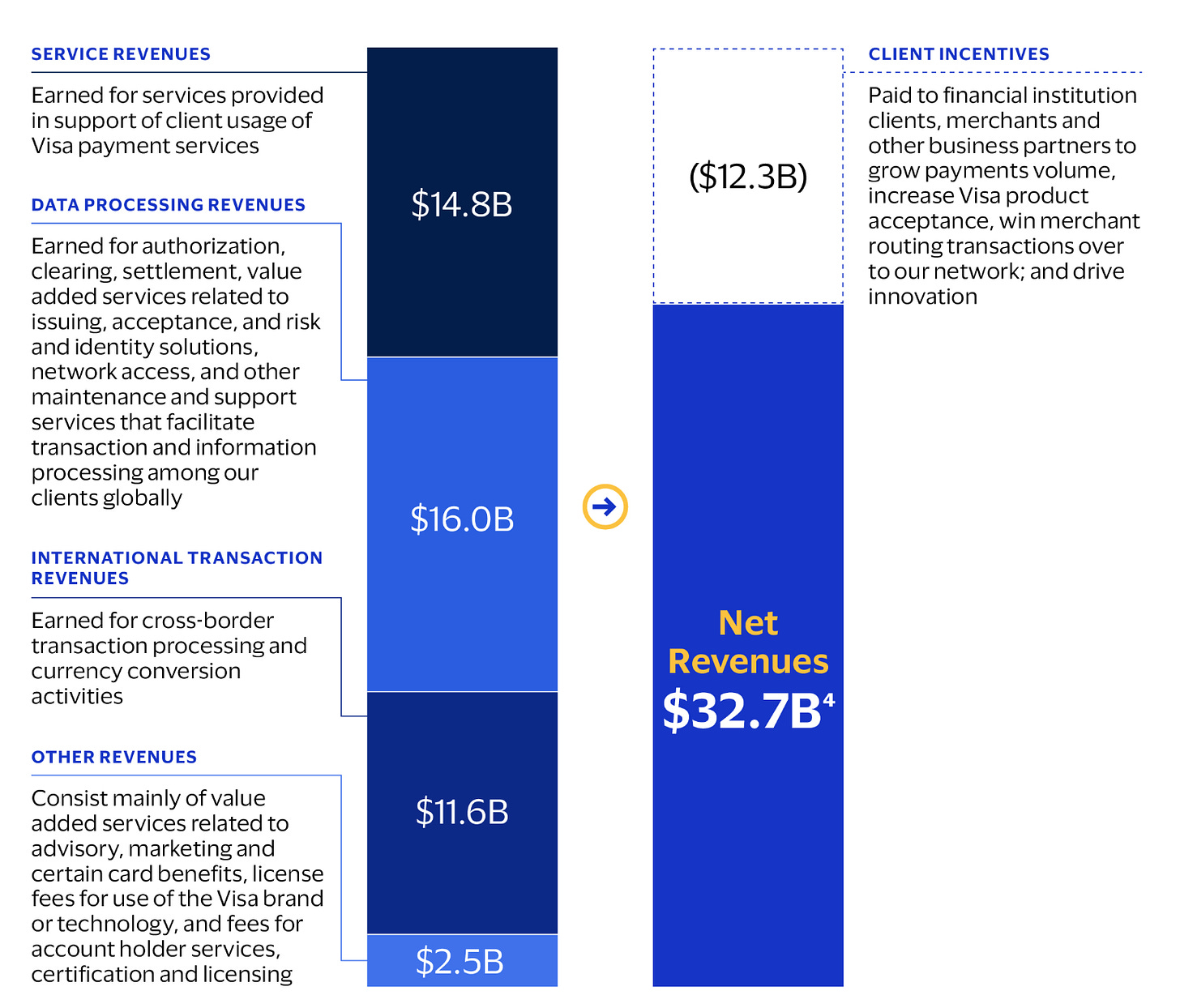

(2) Network Incentives

Alongside the card issuing agreement every fintech gets into to earn interchange is their most prized possession that only some will earn - their payment network marketing incentives agreement. Per Visa, “client incentives are paid to business partners to grow payments volume, increase Visa product acceptance, win merchant routing transactions to our network, and drive innovation.” What this amounts to in dollar terms is that Visa paid out ~27% of its gross revenue in client incentives in 2023 - a whopping $12.3bn. As a percentage of volume (12.3T in payments volume on credit and debit), it’s about 10bps per dollar spent, on average.

Given we’re talking about Robinhood rather than any average merchant or issuer, given that it’s credit vs debit and it’s an opportunity for Visa to win business from other premium cards for prime/near-prime cardholders, it wouldn’t be surprising if their incentives agreement was ~2-3x the average, and potentially even higher.

For simplicity, we’ll assume it’s 2x the average or ~0.20%. So we’re now up to 2.80%.

Meanwhile, the left side of the equation doesn’t capture all that’s left for cashback rewards

(3) Merchant Funded Rewards

Now that we’ve covered the right side of the equation, the other missing piece is our assumptions on what rate Robinhood actually needs to meet to cover their cashback rewards rate. It’s easy to think it’s 3%, because that’s the headline rate.

But the reality is that Robinhood is funding at least some part of that 3% cash back rate from merchant-funded rewards. As I mentioned in my post about Chime Deals and Robinhood’s Cash Card, merchants are willing to fund some of the cashback rewards as a way to drive incremental sales via platforms like Upside and Kard.

You’ll often see these cards require you to activate offers at select merchants and/or work through a rotating selection of merchants to be eligible. Figuring out the blended merchant-funded cashback rate is difficult given merchant and spend mix, but there’s a few ways to triangulate.

The first is top-down - it seems reasonable to assume these merchant-funded rewards are at least 3% (anything less than that and the offer stops being anymore compelling than your average cash back rewards), and conservative to assume that 10% of spend volume will go through these merchants, resulting in 3% * 10% = 0.30% of blended cashback.

Another way is to actually look at debit cards with rewards, because debit card interchange is so low that the only way to offer rewards is likely through merchant-funded rewards. If you’re not maintaining a minimum balance, Axos Bank gives you 0.50% back, but only on signature based transactions, which, based on my post about debit card interchange, is ~64% of spend mix so 0.50% * 64% = 0.32% blended cashback. There’s an argument to be made that credit card cashback could be higher than debit given overall purchasing power and consumer type, but let’s stay conservative at 0.30% cashback for now.

That means that instead of the 3% cashback, I actually only need to get to 2.70%, because merchants will fund some of my carrying costs.

And with 2.80% of interchange + network incentives, I’m already in the clear! But there’s more because we haven’t even gotten to the best element yet - redemptions.

(4) Redemption Options

Why are we talking about redemptions when it’s a cashback card you ask?

Because, it’s technically not a cashback card, at least not upfront. The way the Robinhood Card Rewards program works is that it’s actually a Points program first, before you can redeem. You don’t just see an instant reduction of your spend by 3%, you need to use your points to do it. And as soon as you incorporate friction, you could see anywhere from 20% to up to 40% of points going unspent every year (yes, technically this is the percentage of cardholders who have unspent points, not the percentage of points that are unspent, but it’s used interchangeably everywhere it’s referenced, and we’ll be consistent in all subsequent math so the difference probably won’t matter). On 3% cashback * 20% unspent rewards, that’s at least 0.60% in unspent rewards.

If you do end up wanting to redeem, you’ll be able to put your points in a couple of places - into either the Brokerage account, the Travel portal, the Shop portal, or the Gift Card Rewards portal (Now Alex Johnson probably realizes why they need another app that probably looks a lot like this one). So how does Robinhood offset these redemptions?

Let’s start with the easy ones first - the portals:

With a Travel portal like this one, Robinhood is becoming the equivalent of an OTA (“online travel agent”) just like Expedia, Booking or Kayak. And industry standard rates for bookings are around 15% or more, so even with the 5% back on travel spend purchased through their portal, they’re still getting a 10% reduction to your points spend.

The Shop portal has similar economics - it’s essentially like if the whole universe of possible spend was merchant-funded and all the merchants were paying the most to get users to spend (think 10-15% on average).

The Gift Cards portal rounds it out with a well disclosed 10-20% margin on the gift cards that are being sold to you.

According to that same study on rewards usage, ~30% of those that redeemed rewards spent it on travel which means 80% rewards spent * 30% spent on travel = 24% spent on travel (here’s the flip side of the technicality where it’s likely that more than 24% of points were spent on travel because what else is there really to spend it on, but we’ll stay consistent). So for every point you spend, Robinhood is getting 10-15% back in offsets which means at 3% cashback, it’s 3% * 24% * 10% = 0.07% in cashback offsetting.

Our last stop on this redemption ride is potentially the most important - redemptions in the Robinhood Brokerage Account. In order to get anywhere close to “cash back,” you need to first convert your points into your brokerage cash account. But once it’s there, Robinhood has all sorts of ways to monetize those points either via trading (and associated revenue via PFOF) or even just sitting in your account (and associated revenue via net interest). Some fintech nerds may call this cross-sell, but given it’s a use of the cards earned from cashback, to me it’s a part of the credit card product and only the incremental usage, beyond cashback points, should be considered cross-sell.

In any case, instead of hand-waving the benefit from this additional usage / cross-sell, let’s calculate the potential benefit. We know Robinhood had an incremental $40bn in assets under custody and over that time they generated a whopping $1.9bn in revenue, leading to a take rate of ~4.75%. So on your 3% cashback where 80% of the rewards are spent and 70% are redeemed for cashback with a 4.75% take rate on cash deposited into Robinhood, we’re seeing another 0.08% cash back offsetting.

So let’s total up the left side of the equation:

3% cashback - 0.30% merchant-funded cashback - 0.60% unspent rewards - 0.07% portal cashback offsets - 0.08% Robinhood usage offset = 1.95% net cashback.

On the right side of the equation:

2.60% interchange + 0.20% network incentives = 2.80% net revenue

So on the standalone business alone, we’re getting a ~30% net revenue margin on 3% cashback. Not bad for the business of free.

(EDIT: An earlier version of this post incorrectly calculated the net revenue margin as a % of net cashback instead of interchange. This margin calculation has been corrected to 30%).

I immediately assumed these cards are loss-generating and treated as CAC...

As usual super interesting!

Would love to hear your take on:

1. The unit economics of Robinhood's IRA match -> seems like RH gold members get 3% which is crazy for me,

2. The big reveal of Visa's unit economics of scheme fees in a similar way to what you just did with IC... Over the summer I spent quite a couple hours trying to figure it out from their annual reports but the breakdown they have with "service revenues", "data processing", "international transaction revenues", etc. is just so unclear. Maybe this would even require a partnership with a huge scheme fee nerd haha

Did I get this wrong. The instruction was to 'apply a haircut to be safe with 15%', but the value was increased by 15% instead of being reduced. Did you mean a markup?